His concepts are so fundamental and widely accepted that he is sometimes overlooked as a historical figure, considered unfashionable in modern discourse.

But were Newton’s breakthroughs purely his own, or were they shaped by the intellectual currents of his time? This exploration delves into the philosophy behind his thinking and the pre-existing knowledge that influenced his discoveries.

They were the first truly universal laws, but formulating them required a radical shift in perspective. Before proposing such a law, one had to believe that all objects—whether large or small—were governed by the same fundamental principles. This idea, though intuitive today, was not widely accepted in Newton’s time. In fact, Aristotle had proposed two distinct types of motion: one governing celestial bodies, which he believed moved in perfect circles, and another for terrestrial objects, which he thought followed linear trajectories.

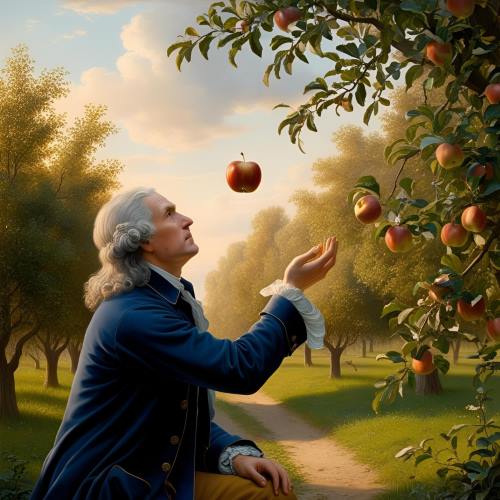

Conceiving an invisible force that governs motion was extraordinary, but recognizing that this force applied universally—to both an apple and the vast celestial bodies—was an even greater intellectual leap. To formulate a true universal law, Newton had to postulate that the apple exerted an equal force on Earth, though negligible due to the planet’s immense mass. When applied to celestial bodies of comparable size, this mutual attraction became significant in determining motion. Without assuming that all objects exert gravitational force, physics would require arbitrary distinctions—an approach incompatible with Newton’s vision of a unified, exception-free science.

French philosopher Renee Descartes proposed that the universe was a machine running in predictable laws rather than the whim of Divinity. While Newton rejected Descartes’ vortex theory of planetary motion, he adopted some of his mathematical approaches and concepts of force.

Galileo’s studies on motion, particularly his ideas on inertia and falling bodies, were foundational for Newton. Galileo showed that objects accelerate uniformly under gravity and formulated the principle of inertia, which Newton refined into his First Law of Motion. However, unlike Newton, Galileo did not have a clear understanding of the distinction between acceleration and velocity.

Fundamental concepts that are widely known and taken for granted today were not understood in Newton’s time. Newton was a self-sufficient genius who developed the mathematical techniques to express his ideas. He developed calculus which was also independently discovered by Gustav Leibniz. These simultaneous discoveries suggest that this was a fertile age for new mathematical and scientific developments.

Although Einstein’s theory of relativity is more complex than Newtonian mechanics, it was built upon existing mathematical foundations. The equations for time dilation, which underpin special relativity, were first formulated by the Swiss physicist Hendrik Lorentz. Similarly, the mathematical framework for general relativity was heavily influenced by the work of Bernhard Riemann, whose concepts of curved space provided the foundation for Einstein’s gravitational field equations.

Huygens provided formulas for centripetal force: F = MV²/R, essential for orbital mechanics.

Newton took Hooke’s idea and mathematically proved that an inverse square law of attraction leads to Kepler’s laws.

His equation: F = Gm₁m₂/r²

He justified it using calculus (which he invented) and his laws of motion.

It is widely believed that many of Newton’s key discoveries emerged while he was quarantined during the plague. In 1665, as Cambridge University closed, Newton retreated to his family home in Woolsthorpe, Lincolnshire—much like the lockdowns of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, while most of us spent lockdown learning new hobbies or perfecting home workouts, Newton redefined science for the next 250 years.

During this period, he developed calculus, formulated his laws of motion, and later published Principia Mathematica in 1687.

"If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants."

In truth, Newton saw farther ahead than any other human.